A recent, unsuccessful bid on a group of Lincoln biblio-books from the collection of Louise Taper leads me here. That, and a rediscovery last week among a group of books I acquired shortly before moving my library three years ago. Both instances germinated an idea into an essay – the early collecting of printed material on the Great Emancipator.

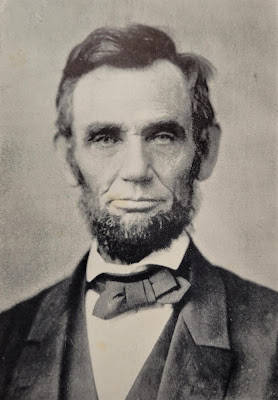

Works by and about Abraham Lincoln, called broadly “Lincolniana,” has been avidly sought by collectors since the Civil War. Lincoln’s life from homespun roots to statesman to martyr has drawn interest from every conceivable angle. Publications abound. As early as 1910 there were already more than 125 separate biographies published.

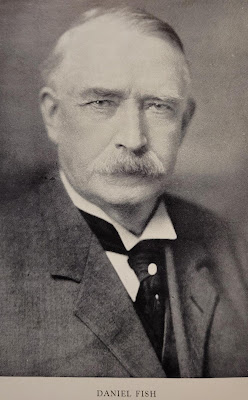

Often when I am doing biblio-research, I’m the first to clear a path (or follow one much overgrown). I soon discovered this was not the case with Lincoln. The early collecting of Lincoln has been documented directly by collectors such as Daniel Fish (1848-1924) and Joseph Oakleaf (1858-1930), and in secondary essays, most notably J. L. McCorison’s “The Great Lincoln Collectors and What Came of Them” (1947).

So, a brief overview is at hand without a lot of hacking through the underbrush. This will be interwoven with my own story of a terrific find. The early groundbreakers in collecting Lincoln material included Andrew Boyd and Charles Henry Hart. Boyd and Hart compiled the first major bibliographic work, Memorial Lincoln Bibliography (1870). These men and others like William Herndon, Lincoln’s law partner and biographer, laid the foundation for subsequent major collectors to follow. The next group of enthusiasts, labeled the “Big Five” each built fabulous collections during the 1890s-1920s. Despite the fierce competition among them, they all interacted as friends and colleagues, each to varying degrees willing to help the others and share new discoveries.

McCorison writes, “Following Herndon and Boyd, the collecting of Lincolniana entered upon its most exciting period—a period dominated by the so-called ‘Big Five’. This period was to witness the more careful definition of what comprised Lincolniana, the rise of specialized collecting, and the creation of those monumental accumulations which have since enriched lesser labors and permanently influenced all subsequent collecting. It is improbable that any one of the collections brought into being by Major William Harrison Lambert of Philadelphia; Judd Stewart of Plainfield, New Jersey; Charles Woodberry McLellan of New York City and Champlain, New York; Daniel Fish of Minneapolis, and Joseph Benjamin Oakleaf of Moline, Illinois could today be duplicated, admitting for the moment that such an endeavor would be desirable. These men were contemporaries and helpful competitors. They were also individualists and each assiduously followed his own bent. Individually and collectively the achievement of these men is so phenomenal that present day collectors look back upon it with wonder and wistful envy. Together, they dominated the field of Lincolniana, almost but not quite – to the exclusion of serious outside rivalry.”

Joseph Oakleaf explains in the introduction to his Lincoln Bibliography (1925) just how this unusual confluence of like-minded collectors interacted, “We five concluded to, and did, establish a ‘Clearing House,’ with Mr. Stewart acting as the corresponding secretary, and new finds by any of us would be reported to Mr. Stewart and Mr. Fish. Thus we knew what each one was adding to his collection, and helped each other in various ways, in order to make the collections as complete as possible.”

I know of no other instance where such a significant group of major private collectors cooperated in similar fashion -- a truly extraordinary circumstance in the annals of American book collecting.

The five collections would all go on to enrich Lincoln scholarship and later collectors. The Lambert and Burton collections were dispersed by auction; the McLellan collection was purchased by John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and presented to Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island; the Stewart collection was purchased by Henry E. Huntington for his library; the Fish collection was acquired by the Lincoln Historical Research Foundation at Fort Wayne, Indiana; and the Oakleaf collection found a home at the Lilly Library, Indiana University.

Daniel Fish and Joseph Oakleaf were the most bibliographical of the group. Fish’s Lincoln Literature: A Bibliographical Account of Books and Pamphlets Relating to Abraham Lincoln (1900, revised, 1906) was a groundbreaking work, influencing Lincoln collecting and bibliography more than any other early publication. Fish established definitions and standards for classifying Lincolniana.

Fish writes in “Lincoln Collections and Lincoln Bibliography” (1908), “Mine is a list of books and pamphlets (and no others) whose origin is traceable directly and exclusively to the life, acts, sayings and death of the man. Variations from the aim are blemishes. Failure to attain completeness in its execution, though unavoidable I suppose, is deeply regretted.” McCorison adds, “Fish was a Lincoln scholar of the first rank and his eminence was everywhere recognized. In his compilation of Lincoln books and pamphlets ‘every reasonable effort’ was ‘made to exhaust the field. . . The leading collections of Lincolniana’ were freely opened to him. ‘The chief libraries of both Europe and America were visited, ‘extensive correspondence. . . carried on, and scores of catalogues examined.’ His bibliography is therefore another bench-mark of permanent significance and ranks among the three or four great works of its kind.”

Daniel Fish was a busy family man, Minneapolis lawyer, and judge, active in numerous organizations, so it is impressive he found the time to heavily indulge his collecting and bibliographic passion. He explains the beginnings of his collecting, “On my way home from the war in the summer of [18]65, while yet in the first half of my eighteenth year, I bought my first book, the very first that was paid for out of my personal earnings not a school book or else a dime novel. It was ‘The President’s Words,’ compiled from Lincoln’s writings and speeches by Edward Everett Hale, now venerable and beloved. If that volume had not been lost prior to 1892, it would have constituted at the beginning of that year my entire stock of Lincolniana. It was then that I was asked by a society of young people to address them upon a topic of my own choosing. The occasion seemed appropriate for a popular lecture on the revered Commander-in-Chief under whom I had served for a brief term as a boy-soldier of the Union. In preparation for that task I read two or three of the leading biographies. Whether my hearers were interested or not, my own enjoyment of the study was intense. Memory recalled the days when Lincoln’s influence, surviving all the vicissitudes of war and politics, had become supreme, and, most vividly of all, the terrible anger of the troops when the news of his murder came to us in the camps of North Carolina. The sources of his power over men appealed to me as even more interesting than the mere events of the great struggle through which he had led us. I afterward bought such books about him as were readily accessible, and out of this came the desire to possess an adequate library on the subject. For a considerable time, however, I sought only biographies, of which there was an astonishing number. Often am I reminded of a first visit to the shop of that delightful old man Charles Woodward, in Nassau street, New York, and his vain offer at a few cents a piece of a hundred or more of the pamphlet sermons and eulogies; treasures which have since cost me as many dollars. Needless to say in this presence, the craving for a complete Lincoln library became seated and I began the effort to find out what such a library should contain. A card catalogue resulted, embracing such Lincolniana as I could acquire or find; and that led to the printed list of 1900, of which 160 copies were made and distributed.

“A leading purpose of that list was to bring to light the many uncopyrighted publications known to exist, but exceedingly hard to uncover. That aim was largely accomplished, but some other consequences followed not quite so pleasing from the collector’s point of view. The enterprise of dealers was stimulated no less than the zeal of rivals. Both supplied me with desired information, but prices soared. I would be the very last to decry the services of that gentle mercenary, your merchant of second-hand books, but one of his virtues is slightly overdone; he appreciates the amiable weaknesses of a collector almost too keenly.”

Joseph Oakleaf was the youngest member of the “Big Five” but he quickly proved himself worthy of his elders. Fish notes in his 1908 essay, “My friend Joseph B. Oakleaf, Esq., of Moline, Ill., is rapidly accumulating a fine Lincoln library. He is our junior, both in age and in the date of entry into this competition, but he is no laggard. From the late advices I judge that he is likely to surpass me very soon, his total being then 743 of the 1,103 published titles, only twenty short of mine. As the baby of our family, he demands, and of course receives the favors due that stage of development, and amply requites them.”

Oakleaf himself tells of his fortuitous introduction to Fish and the beginnings of his Lincoln collection in “Hobbies: An Address on the Collection of Lincoln Literature” (1923), “I thought I would like to have all the biographies of Lincoln, at least, and I then concluded that a hundred volumes would probably be the extent of my library. I began collecting in a modest manner and did not correspond with any one who was collecting, nor did I know of any one who had the hobby. I made notations from the foot notes of the work of Nicolay and Hay and I went to our Public Library and finally my name became known to the old book dealers and I received catalogues, and then my hobby really started. . . . My gala day came at the close of the year 1900. It was while visiting with genial Frank M. Morris of Chicago, in his famous book shop, that he informed me that a man by the name of Fish of Minneapolis had compiled a bibliography. Upon my return home, I wrote to the Hon. Daniel Fish, with a great deal of misgiving, and inquired as to his bibliography, and out of the goodness of his great heart he sent me a copy of Lincoln Literature. If I had known how extensive a complete collection of Lincolniana would be when I first began collecting, I am satisfied that I would not have had the heart to begin the work.”

Oakleaf was tenacious in tracking down Lincolniana. He writes, “When I started in my collecting I had no one to go to for information, but if I heard that an item was printed in a certain place I wrote to the publishers for information, and if I got no reply I wrote to the postmaster of the town, and sometimes I wrote eight or ten letters for a commonplace item, but I generally got it. The pursuit of an item has been very pleasant to me.” His collection would eventually contain over 8,000 volumes.

Oakleaf and his mentor Fish were soon exchanging bibliographical information and collecting news. Fish would introduce Oakleaf into the circle of the other four major Lincoln collectors. One was Judd Stewart. Oakleaf records, “My collection of Lincolniana was known locally, and at one time I appeared before the high school of our City to say something about Lincoln. At that time I tendered the use of my library to any one who desired to make a research, and young man by the name of Philip Joseph availed himself of the opportunity and delivered an oration entitled: ‘The Fame of Abraham Lincoln.’ The paper was well written, and I had it published for him and sent a copy to Mr. Fish, who asked me to send a copy to his good friend, Judd Stewart. This I did, and in that way reached the heart and hand of that genial Lincoln enthusiast.”

The Fish-Oakleaf friendship deepened, and the two men visited each other and travelled together in search of Lincoln. Oakleaf says all too briefly, “Hon. Daniel Fish, of Minneapolis, whom I have had the pleasure of entertaining in my home and with whom I have made a trip through Lincoln country.”

Oakleaf sent a letter to Fish on July 28, 1920, after the untimely death of Stewart, "Now, you and I are the only ones left of 'The Big Five.' I don't want to lose sight of you, and I hope you won't forget me."

The culmination of the Fish-Oakleaf friendship would occur shortly after Fish’s own death in 1924. Oakleaf had been working for years on compiling a supplement to Fish’s bibliography. Oakleaf published it in 1925 as Lincoln Bibliography: A List of Books and Pamphlets Related to Abraham Lincoln. Oakleaf provided not only bibliographical material, but also profiled each of the “Big Five” collectors with their portraits, rare photographic images of Lincoln from the collection of Frederick Hill Meserve, and an introduction by Henry Rankin, who met Lincoln at the age of ten and later became a law student in his office. Oakleaf’s book is a highly sought Lincolniana item in its own right. (And scarce, too, limited to 102 signed copies.)

Oakleaf writes in his profile of Fish, “The passing of Judge Fish was a personal loss to the compiler, who expected to have him pass upon the manuscript of the bibliography before it went to press and to get the benefit of just criticism.”

Some subscribers to Oakleaf’s 1925 Bibliography assumed that the original Fish list would also be included. This confusion resulted in Oakleaf republishing at his own expense Fish’s already scarce original edition as a companion volume a year later, A Reprint of the List of Books and Pamphlets Relating to Abraham Lincoln Compiled by Daniel Fish of the Minnesota Bar in 1906 (1926).

Oakleaf explains in the introduction to the Fish reprint, “I answered every one that I did not propose to filch from my friend, Daniel Fish, the honor that belonged to him and which is enduring, Mr. Fish being an outstanding figure in the book world as the original bibliographer of Lincoln Literature.

“Mr. Fish passed to the Great Beyond in February, 1924, and was laid to rest in a cemetery at Minneapolis, on Lincoln’s birthday.

“At the solicitation of many subscribers who have been unable to obtain the Fish bibliography in separate form, I have concluded, with the consent of Mrs. Fish, to reprint it. . . This reprint, like my bibliography, is a labor of love; my work must be paid in gratitude, which I consider is sufficient compensation.”

None of this information was top-of-mind to me, nor apparently the seller, when I purchased during the midst of a move in 2018 a first edition of Daniel Fish’s Lincoln Literature (1900). I glanced at the book briefly before putting it into a box. But the distractions of moving my entire library vanquished the book from my thoughts. Recently, I was organizing some uncatalogued acquisitions from the time of the move. And Mr. Fish made his welcome reappearance, soon to great fanfare after I looked closer at my find. (I let out a hearty huzzah!) For the copy bore the bookplate of Joseph Benjamin Oakleaf, his ownership signature, and his extensive annotations – certainly the copy sent by Fish to Oakleaf in 1900 that ignited their fruitful friendship and guided the early formation of Oakleaf’s collection.

Joseph Oakleaf in his “Hobbies” essay sums up the general feeling that many of us, including myself, would agree with, “Not only has the collection of Lincolniana been a pleasure to me, but the acquaintance that I have formed through my hobby is really worth to me many fold more than my collection.”

And as Honest Abe himself said, “The better part of one’s life consists of his friendships.”

Wonderful, Kurt - and a great discovery! I especially enjoyed Mr. Fish's comment regarding "merchants of second hand books," and the "amiable weaknesses of collectors!"

ReplyDeleteThanks for reading. I also found Fish's comments entertaining and spot on.

DeleteKurt,

ReplyDeleteWhen I lived and worked in Chicago, Torch Press Books were fairly common (Iowa is not that distant) but I never saw the Oakleaf bibliography. I have a copy of the Oakleaf bookplate in my collection. FWIW, it matches yours perfectly.

Thanks for a great essay.

Bob M.

Most of the copies of the Oakleaf bibliography have probably migrated to libraries by now. Thanks for your comments!

ReplyDeleteKurt,

ReplyDeleteFantastic article. In my A H Greenly research I soon started coming across all things Lincoln, and these 5 men are the foundation of where Greenly's generation of Lincolniana collectors started. I can only guess he likely folded into his collection, some of the Lambert and Burton material.

I'm thankful for the sharing of your associations and the evolving bibliography over time. It helps bring all this together; even for me out here in the Pacific Northwest Americana edge of the book world.

Tom.

Hi Tom, Thanks for reading and your kind comments. Keep up the research on Greenly! Tell me all about it when you have time.

DeleteAbout 30 years ago I was researching A. Edward Newton at the Free Library of Philadelphia's Rare Book Department. I was looking for a specific item listed in the catalog. The librarian found a reference to the item's being on a specific shelf, and pulled out an envelope from the shelf. It turned out to be a Lincoln letter, not the AEN item...My closest connection to Lincolniana.

ReplyDeletePS The Free Library has everything of interest left at AEN's residence upon his death, and donated by his son.